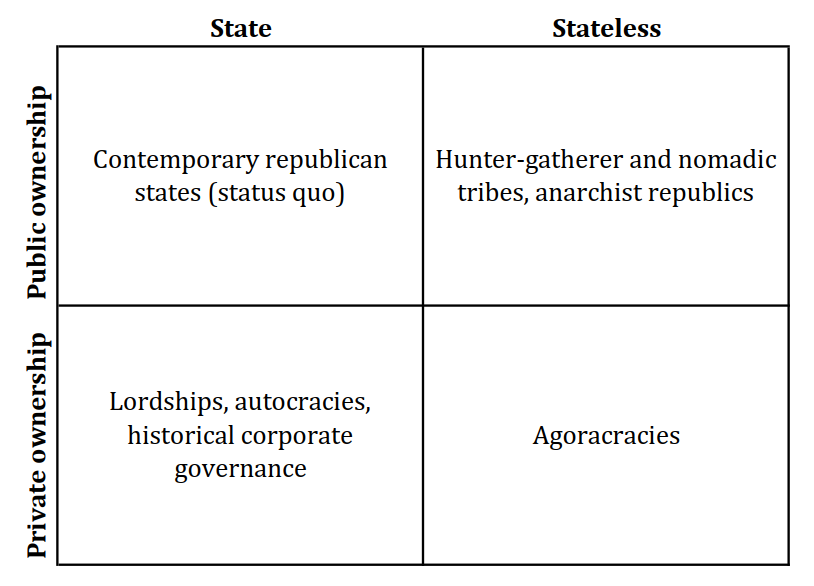

The four systems of governance

[On Power]

The 20th century has spawned a monopoly on governance. With its powerhouse economy, cultural institutions, and unrivaled military, the U.S. has managed to completely dominate the world for a century. The U.S. victory of WWI and WWII has allowed them to "export democracy" to Europe and, consequently, the world which Europe subdued.

How has this project worked out? African republics are rife with petty corruption, China and Russia are republican façades, South Korea impeaches every other president, strongmen swing left and right in Latin America, and the western democracies have completely fallen out of the hands of its citizenry. I will not pretend that states like Iran and Saudi Arabia have fared much better; the political problems which exist there are just distinct from the democratic states.

I am writing this article simply to remind that differing systems exist, some of which have not been explored for a century or ever in history. These systems do not work uniformly across all nations or countries either. What works best in a particular area would depend largely on its history and socio-economic conditions. If anything, I believe in a flexible, competitive approach to governance around the world in opposition to the utopian monopoly which republicanism has had in recent history.

Reframing governance and the state

"Governance" is an unfortunately underused word. As a first step, think of governance as the service given by a "government". This includes the bare bones like military, police, and courts. In more contemporary times, this also includes social welfare, regulation, national parks, and others. Various governments employ governance with differing services. The best way to think of governance is as a varying collection of services which is generally administered by the "government".

The "state", whose modern form did not really come about in the western world until the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648, is an institution which centralizes these services into a singular entity. However, one should note that many of the services that modern states provide today were previously provided outside of the state. For lack of a better standard, I believe the distinction from "state" to "stateless" should be in the absence or outsourcing of the military, police, and/or courts (for lack of their existence or lack of its centralization).

Public-State

The public state is certainly the most familiar to anyone living in the last century. Republics, originating from the term res publica or publicly owned, dominate the world today to varying degrees of success. It consists of centralized services indirectly chosen and administered under many rulers, typically a citizenry. Despite its popularity, most states fail in their public ownership as they are hijacked by various oligarchic factions, for the better or worse. The success of a public state is largely dependent on the virtue of its citizenship to avoid corruption.

Historically, public states were much smaller. While their total lands may be vast, the citizenry of the ancient Roman Republic and Athens were once limited to just a small (by modern standards) city. It worked partially because people knew each other, trusted each other, and were willing to sacrifice for the common good of their neighbors. As the citizenry expands (numerically and geographically) and breaks down, the public state ceases to be public and moves into "the gray area", as it had historically.

Public-Stateless

While governance is administered by a single entity or many, stateless public societies do not systemically administer governance whatsoever. In place, it's completely based on individual governance and the social trust that exists between those individuals. If governance is administered, it is to be administered by a mob. Consequently, it necessitates a very small population. According to Andrew Heaton in his book, "Tribalism is Dumb", one member of a tribe or group ceases to know all their members once that group reaches approximately 150 people. This may or may not be a generous limit for a functioning stateless public society, failing to account for intra-family feuds and conflict.

Public stateless societies generally have taken the form of a hunter-gatherer/nomadic tribe or anarchist republic. To exemplify the less familiar "anarchist republic", the Republic of Cospaia flourished in Italy from 1440 to 1826 without any systemic government. Instead, a Council of Elders with no real enforcement mechanism was trusted to make decisions for the republic. Cospaia became wealthy off of a local monopoly on the tobacco trade. It only had a population of approximately 250 inhabitants. For a less obvious example, many small towns across the world are effectively public stateless societies of their own. While they may under a state and have a local sheriff or court, the trust between close-knit inhabitants renders them unused.

Private-State

Private states may be owned by one person as a sole proprietorship or a group of people in the form of a joint-stock company. Rather than trust and a shared desire for the common good, the efficiency of a private state is more based on a profit motive for the owner(s). As a result, I imagine it could be a particularly effective solution for a public society whose trust has broken down. Since the wealth of the state owner is tied to taxation, and consequently the wealth of its inhabitants, the owner is incentivized to promote policies which maximize the wealth of his inhabitants in the long term. By keeping his country safe and stable, the state owner encourages long term investment, resulting in more gold in his treasury. If the state owner begins to mistreat and abuse his inhabitants, the resulting emigration reduces his income. However, still a state, the owner may just force his inhabitants to stay as North Korea does today. As a result, a private state should still have a somewhat benevolent leader to be effective. In contrast to the public systems, a private state can scale more effectively since it's not reliant on a close-knit, smaller population. It is no coincidence that the transition from republic to empire necessitates an emperor to maintain itself.

Historically, private and partial-private states have been relatively frequent. A strong king or lord is effectively a private state owner. However, instead of the state being bought and sold, it was generally passed through a familial dynasty. This had the effect of retaining a degree of virtue via familial teachings while sacrificing efficiency in management. Note that post-Roman, pre-Westphalia Europe was much more complex, and services were shared among the king, lords, and papacy which resulted in a pseudo-stateless society. Perhaps a better example, joint-stock company states were fairly common during the mercantilist era of Europe. The Dutch Cape Colony ruled South Africa from 1652 to 1806 and was governed by its shareholders in the Dutch East India Company. While the Dutch Cape Colony was not super profitable, it was stable. However, it was particularly exploitative. As recorded in 1797, approximately 70% of its population were slaves. The native Khoekhoe people were dwindled with smallpox and were pushed northward by the Dutch East India Company.

While not states in a pure sense, many of the original Anglo-American colonies were either independent sole proprietorships or joint-stock companies. The Virginia Company and Massachusetts Bay Company were governed by a board of shareholders. The Virginia Company focused on resource extraction instead of permanent settlement, resulting in a lack of women. It went bankrupt quickly amidst war, disease, and famine. The Massachusetts Bay Company, with their focus on peaceful settlement, was much more successful before their charter was revoked and they merged with the Plymouth Colony. With regards to sole proprietorships, Pennsylvania was founded and governed by William Penn as a business, political experiment, and home for Quakers. Maryland was founded and governed by the Calverts in England as a business and Catholic enclave. Maryland and Pennsylvania were both profitable projects which resulted in successful colonies for its inhabitants.

Private-Stateless

Private stateless societies have been, without a doubt, the least frequent of the four. In fact, it lacks a good word to describe it. "Anarcho-capitalist society" is a lengthy term and jumbled in its meaning and "private law society" is similar. I prefer to refer to this system as an "agoracracy" or "rule-by-market". In contrast to the private state, the agoracracy has a landowner who does not directly administer essential governance services (police, courts, and/or military). Rather, these services are outsourced to other companies. Similar to the private state, the landowner may be a sole proprietorship or joint-stock company, and is also incentivized to efficiency for profit. Unlike its state counterpart, a web of contracts and insurance prevent the landowner from forcing inhabitants from leaving (see Chaos Theory by Robert P. Murphy for a much more in-depth look at this complex system). Consequently, an agoracracy should not necessitate a "benevolent owner" as much as the private state.

Unfortunately, the examples of agoracracy are very few, but the American not so wild, wild west had elements of agoracracy. While cattleman's associations and mining guilds could have their own means of police and military, many hired external providers like bands of roaming cowboys and range detectives. One notable company and provider was the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, which still exists today. External courts were also sometimes used to settle disputes.

Why are there not more agoracracies? Compared to public stateless societies and public states, capitalist private states were a more recent phenomenon with the emergence of capital. This holds true with agoracracies, too. In contrast to private states, agoracracies can only exist if the service providers exist. For the service providers to exist, a profit motive must exist. However, modern public states are not exactly jumping at the opportunity to sell some of their sovereignty to a company (at least blatantly). As a result, there is no market demand for these companies to exist. For agoracracy to grow, a network of private states may be a necessary precursor.

The gray area

Was the Roman Republic under Caesar a private state? Are short-term dictatorships private states? These states would be in the gray area. While they may be private states in effect, their institutional power is not truly seen as legitimate. More so, it's either a transition phase or temporary lapse which causes instability. Without legitimacy, inhabitants become uncertain about future outcomes and base their decision-making off of short-term, rather than long-term patterns. To be certainly categorized, the rule should be seen as legitimate.

As expressed above, modern public states are also in the gray area. While nominally "public", a weakened citizenry has surrendered much of the power to oligarchic factions, putting them somewhere in-between public and private states in effect. Though, the oligarchic factions lack the same positive incentive structures that a private state owner would have.

Also expressed above, the Middle Age is similarly complicated. Sovereignty was distributed among different levels. Trade federations and lords often existed between kingdoms whereas merchant-run free cities littered various kingdoms and may or may not be tied to a lord. The papacy also had immense political influence, only to be further complicated by the Great Schism of 1054 and the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century. A medieval lordship and/or kingdom cannot easily be placed since the level of sovereignty must be determined first.

Putting things in perspective

In the Bronze Age and Iron Age, public stateless societies dominated before early non-capitalist private states caught up (Egypt, Assyria, Babylon, etc.). During early Classical Antiquity, public states flourished with Rome, Greece, and even Carthage. Late Classical Antiquity saw the return of a non-capitalist private state in the form of the Roman Empire. The Middle Age muddied the waters with sovereign indeterminacy before the Modern Age brought about the return of public states in the form of Rome and Greece.

We are not at the end of history. History is ever-changing. The public states are losing their identities quickly and their inhabitants are worried about instability. Perhaps we will see a return to the complex political system of the Middle Age? Or maybe private states will make a resurgence and cause the blossoming of agoracracy. Regardless, it's not like we have much of a say in our public states.